A Dignity Still to be Determined

Tuesday, April 9, 2024

Reading the Declaration on Human Dignity (“Infinite Dignity”), issued by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) yesterday, reminds me of an old teacher-student story. A student submits an assigned essay, and the teacher returns it with the comment, “What you’ve written here is both good and new. Unfortunately, what’s good in it is not new, and what’s new is not. . .” But let’s break off the story there. And following the Christian rule of charity in all things, say of the Declaration, what’s new in it is . . . yet to be determined.

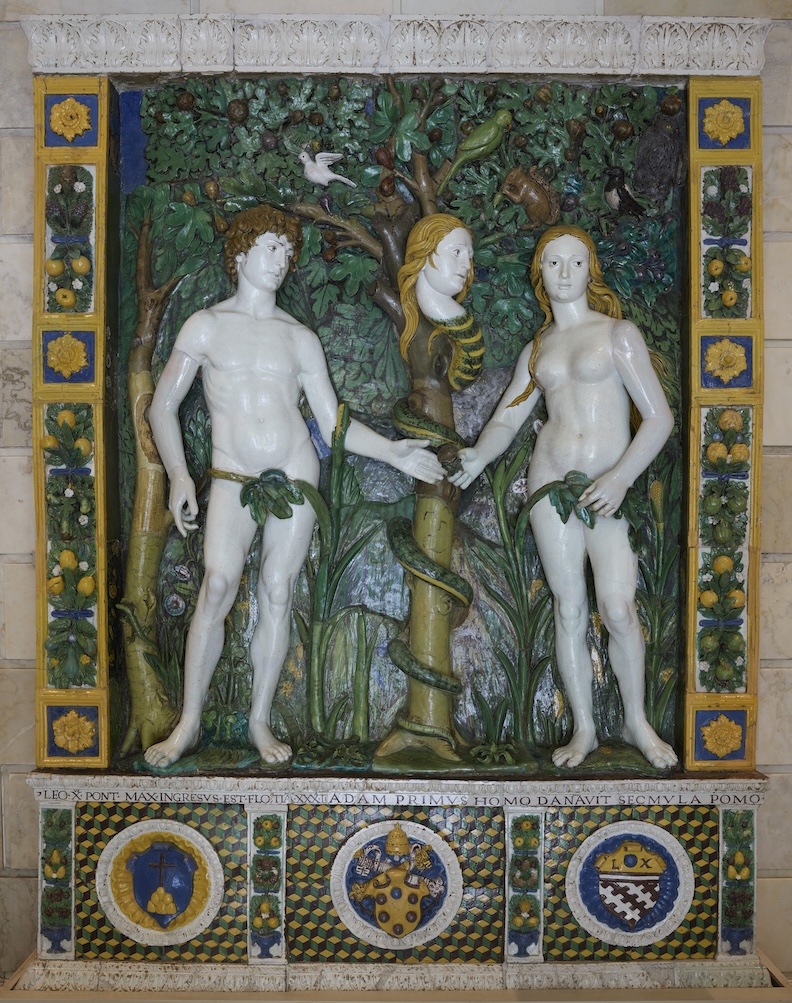

Because in roughly the first half of its sixty-six paragraphs, the document seeks to situate itself in line with recent popes and classical Catholic teaching. It cites Paul VI, JPII, Benedict, Francis (about half the citations, of course). And in a footnote even reaches back to Leo XIII, Piuses XI & XII, and the Vatican II documents Dignitatis humanae and Gaudium et spes. At the press conference introducing the Declaration, Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, head of the DDF, made a point of opening with the observation that the very title of the text came from a 1980 speech St. John Paul gave to a handicapped group in Osnabrück, Germany. Indeed, said the Cardinal, it’s not by chance that the document is even officially dated April 2, the 19thanniversary of JPII’s death.

All of this cannot help but make the alert reader think that the drafters – and those who approved the final text – wanted to frontload ample exculpatory evidence against any objections that might follow.

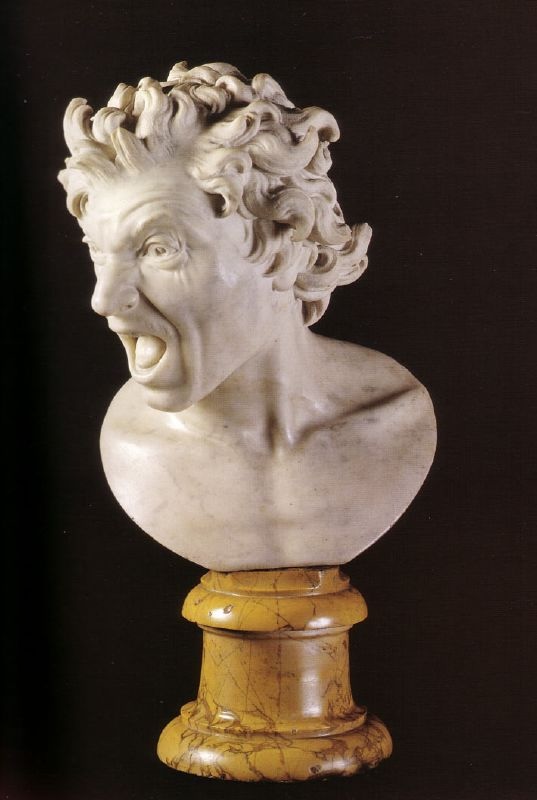

And inevitably, objections will. Because in several respects this apotheosis of human dignity raises more questions than it settles. (“Infinite” human dignity in JPII’s hands was one thing; now, it may mean something very different.)